Payoff for LA Teens’ Hard Work: Scholarships to USC

Three LA siblings become first-generation college students thanks to the Neighborhood Academic Initiative.

Wendy Garcia-Nava treasures a faded snapshot taken when she was a fourth grader. She’s standing in Pardee Plaza, shyly waving at the camera. Her T-shirt reads: “I’m going to college at USC.” It was admittedly a boast. Though she lived only a mile from the USC University Park Campus, the gulf between home and higher education spanned far beyond a few city blocks. Her family squeaked by mostly on her father’s income as a gardener. Neither of her parents had studied past elementary school.

Her T-shirt reads: “I’m going to college at USC.” It was admittedly a boast.

Yet in May, she marched with cap and gown as a graduating senior alongside her Trojan classmates at USC’s 132nd Commencement. An honors student majoring in psychology at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, the 22-year-old also completed three minors: forensics and criminality, Spanish, and computer and digital forensics. She hopes to study law next year. Her two younger brothers aren’t far behind. Jesus Garcia Jr. begins his senior year as a computer science major at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering this fall, and Bryan Garcia, undeclared but leaning toward economics, heads into his sophomore year.

How did one family send three children—their first generation to go to college—to USC on a gardener’s salary?

The Garcia children are products of the Neighborhood Academic Initiative (NAI), USC’s college-access program run in partnership with Los Angeles Unified School District, which includes Murchison Elementary and El Sereno Middle School in east LA and the James A. Foshay Learning Center, a K-12 public school in south LA. Upon graduation from Foshay, all three siblings received admissions offers from USC. They also earned a full-tuition scholarship—the program’s biggest perk.

“I am forever in debt to them,” Wendy says, passion flooding through her voice.

Only one in every 12 students from low-income families in the United States completes a four-year college degree by age 24, according to the National College Access Network.

NAI has changed that in the neighborhoods around USC.

NAI scholars who graduated high school in May: 63

Established in 1991, the program guides students through seven years of rigorous after-school tutoring, Saturday classes and summer sessions. In ninth grade, students start four years of honors and Advanced Placement classes, which are taught daily at USC, often barely after sunrise.

Over the program’s life, 99 percent of its students have graduated high school and entered college, and 83 percent have entered four-year colleges as freshmen. Many of them stay on at USC. Last year, 118 NAI graduates were enrolled as Trojans, including 20 freshmen, making Foshay USC’s No.3 feeder school for 2014.

USC Alumni who are NAI graduates: 357

NAI’s most remarkable feature, according to Thomas S. Sayles, USC’s senior vice president for university relations and himself a south LA native, is that it “doesn’t cherry-pick the best students.” It’s open to almost anyone. A minimum 2.75 GPA is all students need to be in the program.

Academic excellence is the goal, not a prerequisite. “I remember the first time that I got straight A’s,” recalls Wendy, who had started high school with mostly B’s. “I thought, Oh my God, I can do this!”

All NAI graduates: 871

Kim Thomas-Barrios ’84, who has been running NAI since 2002, often sees students like the Garcias seize the college-prep opportunity and go on to university success. Asked to name NAI’s most impressive graduates, Thomas-Barrios balks. “There are so many who have done so much,” she protests. But Sierra Williams is surely one. In 2014, she got offers from 10 schools, including New York University and Carnegie Mellon. She chose USC. In 2012, twin brothers Jesus and Arnulfo Moran were scooped up by Harvard and West Point, respectively. More than 800 NAI graduates have finished college and now work in fields from law to medicine, from dentistry to social work. Many are giving back to the south LA community as well.

You could call the Garcias the unofficial poster family for the program.

Bryan and Jesus Jr. tutor NAI scholars in the afternoons and teach pre-calculus and calculus in the biweekly Saturday Academy. Jesus Jr., who played trombone at Foshay, volunteers his time building a website for the school’s music department. Each fall Wendy talks about the realities of college life with Foshay’s roughly 160 graduating seniors. She’s also involved with the USC-NAI Theater Workshop, an outgrowth ofthe NAI Advanced Placement English classheld at the University Park Campus every morning. All three Garcias fell in love with the stage through this program, which is why Jesus Jr. founded a USC booster club to support it.

Bryan and Jesus Jr. tutor NAI scholars in the afternoons and teach pre-calculus and calculus in the biweekly Saturday Academy. Jesus Jr., who played trombone at Foshay, volunteers his time building a website for the school’s music department. Each fall Wendy talks about the realities of college life with Foshay’s roughly 160 graduating seniors. She’s also involved with the USC-NAI Theater Workshop, an outgrowth ofthe NAI Advanced Placement English classheld at the University Park Campus every morning. All three Garcias fell in love with the stage through this program, which is why Jesus Jr. founded a USC booster club to support it.

Their mom, Isidra Nava, is equally committed. She serves on the NAI Parents Leadership Board, and on Saturday Academy days, you’ll find her at the parent sign-in table doling out advice—even though her own children have already moved on to USC.

“They’re just stellar,” says Thomas-Barrios of the Garcia family. “If there’s something to do, they’re there.”

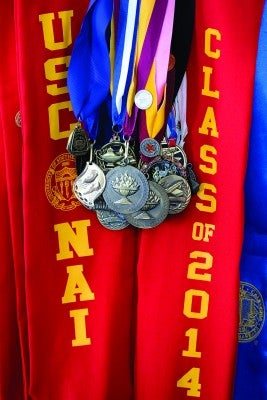

Isidra beams as she welcomes a guest into her one-bedroom cottage about a mile west of USC. She and her husband raised four children here. Academic medals and trophies adorn every nook. She flashes a jaunty grin, though life hasn’t always given her reason to smile.

She made her way alone from Mexico 30 years ago seeking a better life, leaving behind two young children. In LA, she had another child before she met and married Jesus Garcia. The couple had three children of their own. When her older kids joined them, the large family squeezed into a succession of small apartments. The Garcias were close and those were happy times, she says. But after a serious workplace accident left Isidra needing surgery and unable to use her arm, Jesus had to stop working to look after her and the four youngest kids still at home. Money grew tight.

Cost to teach an NAI scholar for one year: $1,480

When Wendy, Jesus Jr. and Bryan were recruited into NAI, they discovered the program would require discipline and sacrifice. Wendy’s passion for Mexican folksinging was the first thing to go: Rehearsals conflicted with NAI’s afternoon tutoring sessions and half-day Saturday Academy.

Every night, the children took over the apartment, spreading their binders and textbooks on the coffee table that doubled as the family dinner table. Studying, always studying, their mom recalls.

“It was a lot of work,” Wendy says. “Friends who weren’t in the program would want to hang out or do other things, and we couldn’t.”

When they weren’t home, the Garcia kids were at the public library. If they needed a computer, they waited their turn for a public terminal. Limited to one hour of computing time a day, they planned ahead for their term papers, pooling and rationing their library login privileges. They worked efficiently—and stayed ruthlessly on task.

All three became excellent students, taking many AP courses and earning mostly A’s. When report cards came home, Mom gave each child a kiss on the cheek and rewarded them with a trip to the 99 Cents Only Store to buy more school supplies.

Getting NAI students ready for college takes seven full-time staff and 120 part-time staff, including instructors, mentors and tutors.

Thomas-Barrios makes a point of hiring tutors who are NAI graduates. They bring an insider’s perspective. “They sat in the same seats, and now they’re teaching. The younger kids see that, and it builds confidence,” Thomas-Barrios says.

NAI graduates are expected to volunteer at least 20 hours a year with current NAI students. But the Garcias give much more than that.

“When we were in the program, we always had alumni coming back to help us,” Bryan says. “That’s why we do the same. We do it naturally, like you would help your family.”

Things could have turned out very differently for the Garcias. When they moved to the neighborhood 20 years ago, their father had no idea there was a university nearby. Looking back, it feels like they won the lottery.

“I can’t believe that all this happened,” Isidra marvels. “I’m very happy.”

As a girl, she had dreamed of becoming a teacher, but she never had a chance to finish school. “Seeing my children’s achievements,” Isidra says, her eyes glistening, “they feel like my achievements.”