Health Ensured: How Affordable is the Affordable Care Act?

The proportion of the national debt tied to health care costs keeps increasing, raising concerns about competitiveness and national security.

At the former clinic of pharmacists Steven Chen PharmD ’89, patients could get in-suite pedicures and valet parking. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Beverly Hills doesn’t just have a reputation for being posh — it’s actually where “Posh Spice” of the Spice Girls, Victoria Beckham, gave birth to her daughter.

Compare that to one of Chen’s first experiences with a patient after he moved to the Weingart Center, a safety-net clinic on Los Angeles’ Skid Row. While Chen was encouraging him to eat more vegetables, the patient cut him off. “He said, ‘Do you realize no one around here has a refrigerator?’ ” Chen recalls.

The experience got Chen thinking about the sometimes-faulty assumptions that health care providers make about their patients. From years of looking at hospital charts, he’d come to believe that too many people end up in emergency rooms or hospitals for a simple reason: They don’t know how to take their prescriptions or are on the wrong ones. “For every dollar spent on medications in the U.S., another dollar is wasted on corrective actions for problems caused by medications,” Chen says, citing data from the Institute of Medicine and the New England Healthcare Institute.

It was a problem familiar to Kathleen Johnson PharmD ’78 of the USC School of Pharmacy. A few years earlier, Johnson began embedding USC pharmacists in local safety-net clinics. These clinics serve the worst off, people who delay care until their conditions are out of control. Pharmacists found patients who’d been prescribed diabetes medications — and didn’t know they had diabetes. Other patients had chronic diseases that could be managed with daily treatment, yet they only popped a few pills when they felt sick

In these clinics, Johnson and Chen began to completely transform what it means to see your pharmacist. The USC pharmacists looked for dangerous drug interactions and wrote new prescriptions (legal in many states including California if the medical facility agrees to it). They ordered lab tests, changed dosages as needed and took people off ineffective medications.

They also got to know their patients, identifying those who’d failed to control their chronic disease over a dangerously long time. The pharmacists called them at home to check on symptoms, and they helped people find ways to get medication for less.

The result: Nearly half of the toughest diabetic patients lowered their blood sugar within six months. Diabetic patients working with a USC clinical pharmacist are four times more likely than similar patients to reduce their blood sugar to recommended levels.

The program’s success — and potential to save money — is precisely the kind of experiment sought under the Affordable Care Act, the 2010 federal law that overhauls the U.S. health care system. Last year, as part of the new law, the federal government set aside $1 billion to fund experiments that could lower health care costs. USC economist Geoffrey Joyce teamed with Chen and Johnson to apply for a grant, with the pharmacists overseeing the program and the economist tracking outcomes.

USC’s proposal was one of only about 100 projects funded nationally. If projections hold, savings from the clinics will exceed $43 million over three years.

Says Joyce: “It’s trying to provide more scientific evidence that coordinated care and addressing chronic disease can both improve care and save money.”

Cutting Costs

These kinds of targeted fixes to the health care system might seem small — especially compared to the $2.7 trillion spent on health care in the U.S. every year — but they’re critical if the Affordable Care Act is going to save money, says Leonard D. Schaeffer, founding chairman and CEO of WellPoint, one of the nation’s largest health insurers, and namesake of the USC Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics. The center is housed jointly at the USC Price School of Public Policy and the USC School of Pharmacy.

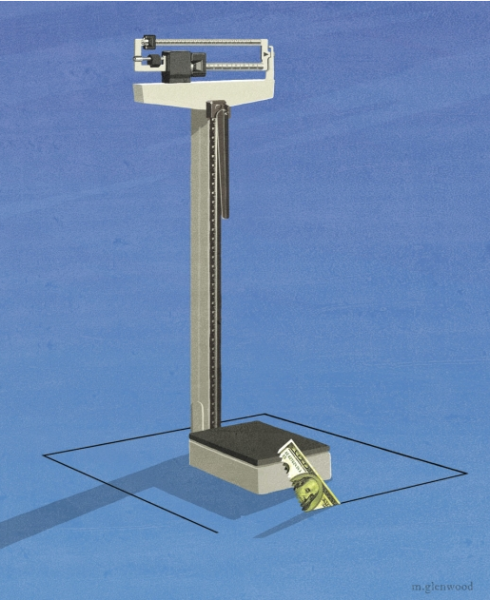

U.S. health care costs doubled over the last decade, growing three times faster than wages and vastly outpacing inflation. The proportion of the national debt tied to health care costs keeps increasing, raising concerns about competitiveness and national security.

Against this backdrop, the Affordable Care Act is poised to go into full effect in 2014. The law includes several methods to cut costs. Chief among them: Make it easy to shop online for insurance through new health insurance exchanges. “For the first time, all Californians will be able to make an apples-to-apples comparison of their health plan choices in 2014,” Peter V. Lee, JD ’93, executive director of the California Health Benefit Exchange, told the Los Angeles Times.

Along with subsidies and the insurance mandate — which will force most Americans to get health coverage — this saves money two ways. It increases the number of young adults (who require less health care) in the health insurance pool and allows people to see a doctor regularly, which reduces expensive emergency care.

But true cost savings are unclear.

“We expect a bump — a pretty significant bump — in utilization, and that’s going to push costs up,” says Michael Cousineau, research associate professor of preventive medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. When people who’ve gone years without medical care finally get insurance, he explains, they tend to need a lot of services.

Massachusetts may be a test case. The state provided near-universal health care to residents in 2006, and spends 15 per- cent more per person on health care than the national average — although spending might be even higher without the system. A 2008 experiment in Oregon — which allowed 10,000 low-income residents into Medicaid by lottery — yielded similar evidence. Greater access to health care saved the state no money, though users spent less out of pocket for care.

Health insurance, it turns out, allows people to use more health care, which then costs more, says Dana Goldman, director of the USC Schaeffer Center and Norman Topping/ National Medical Enterprises Chair in Medicine and Public Policy. “When people get sick and don’t have health care, they don’t get treated, and then they die. And that’s cheap.”

It’s difficult to decide between necessary care and excessive care, and not just at the end of life. In graduate school, economist Neeraj Sood of the USC Schaeffer Center developed a rash and insisted on a referral to a dermatologist. His primary care physician relented, but the next available appointment was in three months. Sood was furious at first, but three months later, his rash had disappeared on its own.

Sood’s example points to the challenge policymakers face in discouraging consumers from unnecessary, costly treatments. There’s evidence that price influences patients’ choices when purchasing drugs, but buying health care doesn’t work the same way as buying a flat-screen television or even a necessity like food. For one thing, insured patients don’t see the full price tag of their treatment. Patients also generally lack the knowledge to make informed comparative decisions about health care, and the sick or injured often are terrified and desperate. “People are not about to negotiate when they’re sick,” Schaeffer says.

Instead, they rely on their physicians’ advice.

Rewards for Smart Care

In study after study, economists have found that physicians respond to economic incentives. When insurers stopped reimbursing as much for cesarean sections, the C-section rate fell. “If you talk to any obstetrician, they’ll say, ‘I would never make a decision about whether to do a C-section based on how much I get paid.’ Yet overall, we know that’s exactly what happens,” Goldman says.

To discourage needless tests and procedures, the Affordable Care Act rewards coordinated treatment through “accountable care organizations,” another potential cost-saving measure. Nationwide, more than 120 such organizations of doctors and hospitals now receive a fixed annual lump sum of federal funds instead of payment every time they order another test. The organizations risk losing money if they go over budget, swal- lowing the cost if they order, say, too many tests. But if they deny you a necessary procedure and you need more complex treatment later, it could cost the organization more.

“Now, all of a sudden, doctors have a new financial incentive to manage their patients’ care to actually keep them out of the hospital,” says health economist Glenn Melnick of the USC Price School.

Crucially, the accountable care organizations will also keep some of the savings if they’re under budget, and this might predispose them to cut salaries or withhold care. That’s sort of the point, but it’s a controversial one.

“Private companies should focus on delivering care efficiently, while government should protect the vulnerable,” says Darius Lakdawalla, USC Schaeffer Center’s director of research. “In an ideal world, efficient care delivery means everyone gets appropriate care at a competitive price, but it remains to be seen whether the Affordable Care Act will allow for greater efficiency in the marketplace.”

The law also changes how safety-net hospitals and community clinics are reimbursed. Right now the government gives them money to help treat uninsured people who can’t pay, but much of that funding will soon be used to pay for the new insurance expansion. In Southern California, many of the uninsured are undocumented immigrants, and they remain without coverage under health care reform. “We have a burden of making sure we have a system in place to take care of those who remain uninsured,” Cousineau says.

Some newly insured who’ve used the public hospital and clinic system may now have a choice and some may opt for the private system over public hospitals. Says Cousineau: “The fear is that the newly insured patients will leave the system and the funding will be diminished, leaving the safety-net health care system without the resources needed to take care of the residually uninsured.”

The Price of Life

At graduation, nearly all American medical students swear an oath that forbids “considerations of religion, nationality, race, party politics or social standing” to intervene between a physician’s responsibility to a patient. Medicine shares a commitment to alleviating suffering, whether among the rich or poor.

Yet can we afford it? This depends on our view of the cost of life and health. Discussions about the health care system are almost never about health care. “They’re about social values. They’re about religious values. They’re about economic consequences. And in the United States, they’re almost always about the role of government,” Schaeffer says. “We think we’re talking about health care, but it’s really about this other constellation of issues.”

Goldman points to HIV as an example of the folly of looking only at health care costs, not health care outcomes. In the early 1990s, treating HIV was cheap. But to an economist, HIV had an infinite cost, “because no matter how much money you spent, AIDS was basically a death sentence,” Goldman explains. Then, in the mid-1990s, highly active antiretroviral drugs arrived. They cost about $15,000 a year and made HIV a chronic illness.

From an economist’s perspective, spending $15,000 to save a life “is an incredibly good deal to society,” Goldman says. “But to policymakers and others, they said, ‘This is a terrible thing! We can’t afford this! They’re the most expensive drugs ever!’ So they tried to ration them because they think they’re expensive.

“They weren’t looking at the price of the health we’re buying. They’re looking at the price of the drug.”

Drugs work. Medical treatments save lives. The U.S., which spends more on cancer treatment than any other country, also has the best cancer survival rates. When the Affordable Care Act goes into effect, 30 million more Americans can get health coverage, including the childless working poor and people with pre-existing conditions. This isn’t trivial.

As Julie Zissimopoulos explains, insurance is meant to be an equalizer, using the comparatively smaller costs of caring for the healthy to balance out the potentially ruinous expenses of others. “That’s what health insurance is supposed to do: protect against those extremes,” says Zissimopoulos, associate director of the USC Schaeffer Center.

But then there’s the reality of finite resources, and the distinct possibility that health reform will fail to stem rising costs. The law, Schaeffer says, is “very artfully done. Assuming everything goes according to plan, the law shouldn’t raise costs. But some of the significant things that are supposed to happen probably won’t.”

Prime among them, he says: 14 tax increases lobbyists aim to repeal.

Health care costs are expected to account for half the national debt by 2040. The Affordable Care Act has an even tighter deadline to stem costs before more drastic measures loom, including across-the-board health care cuts. At that point, centuries of accumulated ethics might falter in the face of politics, money and the toughest calculation of all: the cold cash value of a human life.

Editor’s note: Kathleen Johnson PharmD ’78, chair of the Titus Family Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Economics & Policy at USC, died after an accident in 2012; her daughter Kimberly started the PharmD program at the USC School of Pharmacy that same autumn.

If you have questions or comments on this article, go write to us.