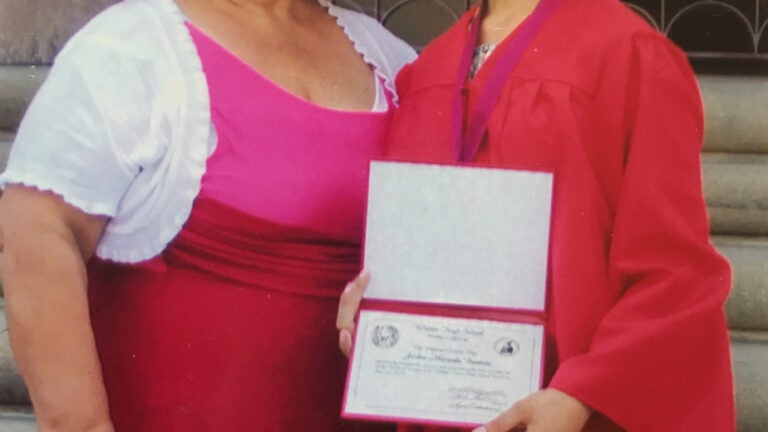

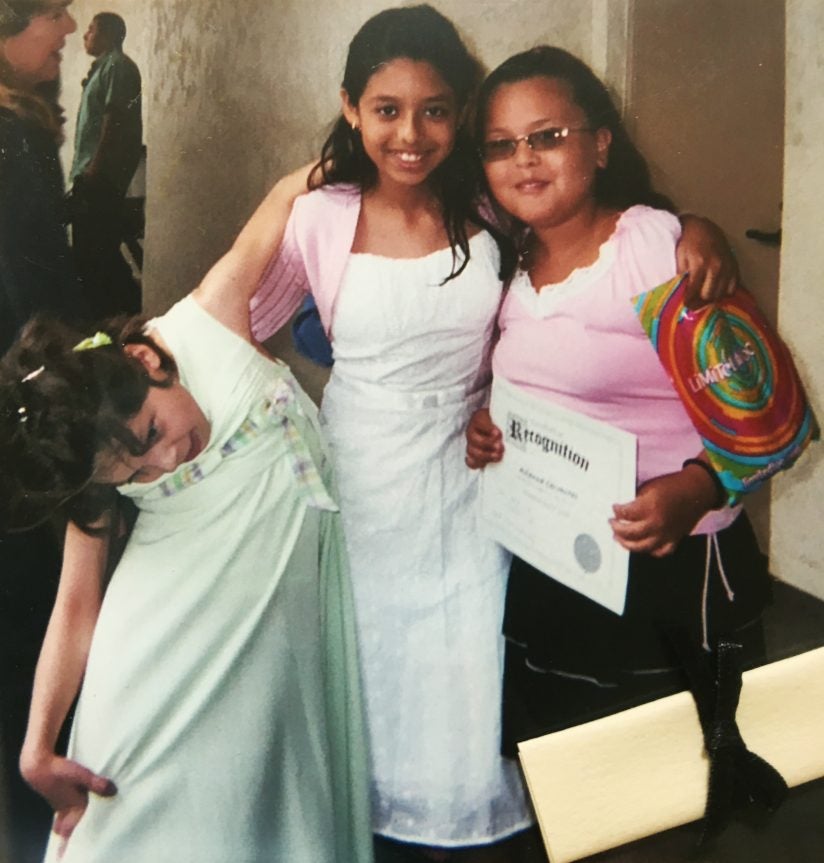

Jordon Bautista had to prop her head up with her knee to do homework as her dystonia progressed. DBS changed her life. | PHOTO COURTESY OF JORDON BAUTISTA

Deep Brain Stimulation and the Girl No One Believed

Wires in the brain bring relief to a Southern California teen with dystonia.

Jordon Bautista’s dystonia appeared when she was a first-grader in Whittier, California. But it took six years for a correct diagnosis.

“I would write and then all of a sudden my hand would jerk out,” says Bautista, now 22. “I would disassociate my body parts. I’d say, ‘It doesn’t want to,’ because it had a mind of its own. I would literally look at my hand and be like, write. And I couldn’t.”

At first, her parents and teachers thought she was faking it. “‘Here goes Madam President again,’ they said. ‘Always in need of attention.’”

Confused and in pain, she taught herself to write left-handed. Then, the dystonia moved up her shoulder. Her neck muscles started to twitch and pull her head to the side. She had to prop her head up with her knee to do homework. Yet early medical visits showed nothing abnormal in her brain.

As the months became years, her condition worsened. Gradually her upper body froze sideways in a rigid 90-degree curve and she had to be strapped to a wheelchair. “My head was literally where my knees were,” Bautista says.

She was eventually diagnosed with dystonia.

In people with dystonia, faulty brain signals cause muscles to spasm and pull the body into twisting, repetitive movements or abnormal postures. It can be caused by an inherited gene, or secondary to damage to the central nervous system or birth trauma. But in many cases dystonia appears mysteriously.

Doctors usually treat the condition with a combination of three approaches: botulinum toxin (Botox) injections, medication and surgery. Medications and Botox helped block the communication between the nerves and muscles to reduce Bautista’s abnormal movements and postures. But the drugs also affected her at school.

Six years after her symptoms appeared, Bautista was cleared for deep brain stimulation, or DBS, in 2008 by Jennifer S. Hui, director of the DBS program at Keck Hospital of USC. Bautista has a vivid memory of the surgery and the “army of white lab coats” congregating to get a good look at her. They’d never seen a case like hers. Bautista’s was the first DBS procedure done at CHLA, with CHLA and Keck School of Medicine of USC neurosurgeon Mark Liker operating.

“I’ll never forget her,” Liker says. “Here was this funny, bright, 12-year-old girl bent at a 90-degree angle to her hips with severe scoliosis. She was in a lot of pain.”

Bautista underwent the standard DBS procedure usually done on Parkinson’s patients at the time: Two permanent wires were placed into her brain in one operation. Liker, who has performed hundreds of DBS procedures in Parkinson’s patients since 2002, and in children with dystonia since 2006, was tasked with planning a trajectory around blood vessels and critical structures in Bautista’s brain before inserting the permanent leads.

“Unlike most open brain surgeries, where everything you’re doing is right there in front of you and you can see it, we’re operating on the unseen brain, because we don’t see the brain at any point during the procedure,” explains neurosurgeon Aaron Robison, who now performs these surgeries alongside Liker at CHLA. “In many ways, it’s an invisible surgery.”

But with the arrival of engineer-physician Terry Sanger of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering and the Keck School of Medicine, doctors now have lots more data to inform their DBS surgery.

Walking! Walking straight. Walking right. Walking upwards instead of sideways. Freedom. You know … I was trapped in a body that I didn’t belong in.

JORDON BAUTISTA

Under his DBS procedure, after a child goes under anesthesia, neurosurgeons insert up to 10 temporary leads in five different areas of the brain. The child is then awakened and kept in the hospital for the next seven days while the temporary leads implanted in their brain record neural activity. Children can sit up, play cards and even drive their electric wheelchairs. Each wire in the child’s brain can have up to 16 little contacts on it, recording the brain on 160 channels.

“We’re listening to the cells,” Sanger says. “And we see particular brain areas fire like crazy every time the child has spasms. So that’s telling us, OK, now we need to figure it out where these are coming from so we can stimulate those areas and turn off the dystonia.”

The recorded signals give Sanger little bits of information that he can piece together and correlate against muscle activity and what the child is doing at any particular time.

For Bautista, the results of her deep brain stimulation were astounding.

Says Liker, her surgeon: “She has a boyfriend. She’s living a full life. If you see her walk into a room today, you wouldn’t recognize her.”

READ MORE

READ MOREFor a Boy Locked in His Own Body, These Doctors Brought Hope

Children with dystonia get up and walk again through science, engineering and a brain implant procedure from a team at USC.

She is now a teacher’s assistant for children with disabilities at the same elementary school she attended. She’s thinking about marriage, about a career as a special needs teacher and becoming a spokesperson for young people with dystonia.

“The teachers can’t believe it’s me,” she says.

When you ask Bautista what she appreciates most of all from her life now, she says, “Walking! Walking straight. Walking right. Walking upwards instead of sideways. Freedom. You know … I was trapped in a body that I didn’t belong in.”

This story was adapted from an article about DBS in the Autumn/Winter 2017 issue of USC Viterbi Magazine.