Can the Book Survive in the Digital Age?

As a digital revolution sweeps through the publishing world, storytelling is alive and well—and English is thriving at USC.

“What do you read, my lord?” Polonius asks Prince Hamlet, in his Shakespearean windbag way.

“Words, words, words,” sighs the young man.

Had The Bard written Hamlet in the digital age, his hipster prince might well have answered: “Tweets, videos, Snapchat photos.”

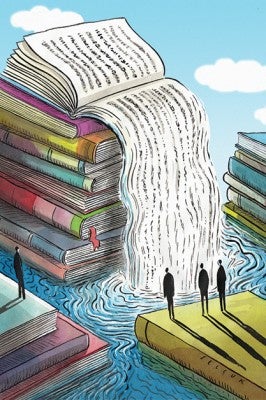

As the palette of today’s media explodes with e-possibilities, words—especially those captured on paper—are no longer the basic unit of storytelling. It’s a turn of events that’s empowering to some and, to others, deeply disturbing.

Some openly fret whether the flowering of the information age spells doomsday for the printed page.

“Within 25 years the digital revolution will bring about the end of paper books,” predicted author Ewan Morrison, writing in the Guardian in 2011. “More importantly, e-books and e-publishing will mean the end of ‘the writer’ as a profession.”

Today, practically anyone with online access can blog or tweet to a worldwide audience. This has both democratized writing and, in some ways, devalued it. At the same time, the rise of digital books and online mega-sellers like Amazon means more writers can self-publish their books, and readers can order books instantly with the push of a button. But authors are getting a smaller piece of the economic pie.

Then there’s the halo effect of social media. Some authors build strong followings on Twitter and Facebook, which bring writers closer to their readers-turned-fans.

In this swirling media landscape, what will happen to the book as we know it?

Read on as three distinguished authors from the Department of English in the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences offer their take on the argument. The gist: Rumors of the book’s demise have been greatly exaggerated.

Can paper survive in a digital-first world?

Leo Braudy: Every time a new technology comes along, there are always people who say the old technology is dead. After photography, people said there will be no more painting. After digital music, they said there are going to be no more analog or live performances. Then there’s always a re-evaluation of the old technology and it gets a glow around it, and becomes a new source of aesthetic pleasure.

When you’re with a book, it is a personal experience, a private experience. There’s a feeling of intimacy that’s right there, embedded in the history of the book, and I think the desire to have that intimate relationship with a work of art is not going to go away.

T.C. Boyle: We can never foresee exactly what is going to happen. When the telephone was invented, people said the great American tradition of letter writing was going to die. And so it did. But who could have predicted that we mainly communicate with each other today through writing, whether Instagram, emails or whatever. People still must write.

My 1987 book, World’s End, has recently been reissued by the Easton Press in a small run as a nice leather-bound book for collectors. So there are people who still want and love a book. The house that I rent on the mountain has a library with a lot of classics of world literature in bound volumes. It’s a great joy to take this big book and put it in your lap and read Dostoevsky again. There’s something about it—it’s tactile—that gives you satisfaction that the Kindle does not.

But Millennials don’t have the same attachment to paper as their parents.

Anna Journey: I think Millennials are aware of the dangers here. They aren’t all screen zombies. They’re hungry for tangibility. My stepdaughter owns two typewriters. Last semester in one of my poetry classes, a word came up in conversation and a student unfamiliar with the term wanted to look it up. Instead of looking at his iPhone, he reached into his jacket and pulled out a paperback dictionary. A poetry acquaintance of mine posted a call on Facebook: “I miss seeing people’s handwriting. Does anybody want to exchange a postcard with me? Message me with your address.” So I sent her a postcard, and she sent one to me. I think there is a hunger for ways of communicating that are becoming foreign. There’s a hunger for using your hands and making a connection. Look at Etsy. Or look at me. I took a taxidermy class a few months ago.

Boyle: I do public readings a lot. I’m looking for a young audience, especially young men who may have played video games but know the novel only as the format for the dreaded term paper, something you do for drudgery in school. I like to give a show, entertain and remind them that literature at its root is a form of entertainment, that it can be cool, it can open up the world to you in a unique way, just as a film or song can.

Braudy: I think there will always be literature because there will always be people who want to tell stories and there will always be people who want to read stories. The question is what format of literature will it appear in? Traditional hard-copy book or online? I suspect it will still be a mingling of the two. I don’t think it’ll be entirely one way or another.

But isn’t digital the environmentally responsible thing to do? Some argue paper made from trees is unsustainable.

Braudy: Maybe we’ll find another material. Who knows? In a hundred years, we could be making books out of air pollution.

Is writing literature a profession?

Braudy: In Britain, yes, but not in the United States. Maybe in New York or a few other places close to the center of publishing, newspapers and magazines, you could put together a life—not a lucrative but a sustainable life—on a freelance basis. Otherwise it’s almost impossible unless you’re a really big seller, like James Patterson or Tom Boyle, or you have another kind of job, usually an academic job.

Boyle: I never dreamed of having a career making money as a writer. It didn’t affect me one way or another. You don’t choose to be an artist. You just are one. Artists will make art no matter what. It doesn’t matter what the public thinks, or what form it’s going to appear in, or whether you’ll make a living. You just do it anyway.

The university has been a blessing for literary novelists and poets in that it has given us a place to be and to cultivate our work and the work of our students. It’s a great thing. I hope it continues.

Journey: I don’t think “poet” is a profession. Poetry is an art; teaching is a profession. Even Shelley back in the 1800s, when he referred to poets as the “unacknowledged legislators of the world,” didn’t consider it a profession. You write because you have to, because you love it, not to sell your poems.

Poetry sales are always modest compared to fiction bestsellers. If a poet sells 5,000 or 10,000 copies of a book, that’s huge, whereas similar numbers in fiction would be cause for shame and despair. There’s a smaller audience for poetry, but it’s vibrant, it’s necessary.