USC Pioneers Live Action Visual Effects

Animators seamlessly meld their work with live action, transporting movie audiences to new worlds.

Quick, can you name the best animated movies you saw this year?

If films like Inside Out or The Good Dinosaur were on your list, you’re not alone. But what about live-action blockbusters like Jurassic World, The Avengers or Mission Impossible?

“Nobody called Avatar an animated film, but it is,” says Michael Fink, chair of the film and television production division of the USC School of Cinematic Arts. In that film, he points out, nearly all the scenes on the planet Pandora were computer-generated with animated performances closely based on the performances of live actors.

Today, movie fans can be forgiven if they can’t tell the difference between animated and live-action films. Films with cartoon characters are easy calls, but what about special effects-laden projects such as Gravity or The Hobbit? They feature live actors shot in front of green screens, and many scenes use computer-generated animated effects that increasingly blur the line between reality and fantasy.

But moviegoers watching a superhero shrink convincingly to the size of an ant or a monster shake its realistic tufts of fuzzy hair might not realize the complexity behind it all. It takes math, computer science and software development—as well as a rich understanding of human emotion, movement and artistic rendering—to bring these characters alive.

And they also may not know the critical roles that the John C. Hench Division of Animation and Digital Arts at the School of Cinematic Arts and several units at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering play in pushing the boundaries of what can be visualized. USC has a reputation as a longtime leader in cinematic arts and game design, but its faculty and alumni are also at the forefront in creating digital humans, virtual reality, 3-D digitization, science visualization and other technology that brings fantasy worlds to life.

A Digital Revolution

It’s a common mistake to associate animation only with kids’ films and TV cartoons, says past Hench division chair Kathy Smith. “The fact is animation is at the core of most digital media creation today.”

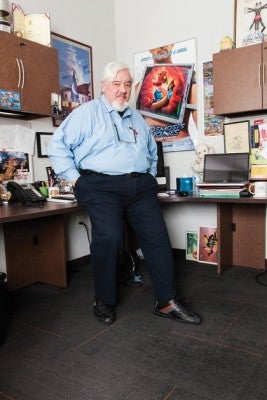

The division’s current chair is Tom Sito, whose career began under the tutelage of the legendary Chuck Jones (think Looney Tunes) and some of the original Disney animators dubbed the “Nine Old Men.” He recently completed a comprehensive history of computer animation, and says flatly: “Animation as an art form has moved into the center of modern digital culture.”

Sito pinpoints the crux of the digital revolution as the period from 1991 to 1995, when films with groundbreaking animated technology such as Terminator, Toy Story and Jurassic Park were released.

“Before that, saying ‘I want to do a movie with computers’ was considered ridiculous,” he says. “After that, not using computers was considered ridiculous.”

At USC, a turning point of sorts may have been reached two years ago when the School of Cinematic Arts’ longtime dean, Elizabeth Daley, named Fink, an Academy Award-winning visual effects supervisor and second unit director, as chair of the school’s production division. His predecessors all had backgrounds in live action producing, but little in animation or visual effects. “It was a pretty bold move on the part of Dean Daley,” Fink says. “She was looking at where media production is now and where it’s going.”

Fink started his USC career in the Hench division, teaching “The World of Visual Effects,” a survey course on the evolution of technology, art and storytelling. In 2012, he started teaching in the production division, inaugurating a green-screen course, “Directing in a Virtual World,” that was instantly popular and has a hefty wait list every semester.

Visual effects supervisors have to work with every department on a production, Fink explains, as they need to know what the director and director of photography are doing and what the production designer and costume designer are planning. They must creatively collaborate with all the production department heads. As Fink describes it: “You have to work with the entire team so that they see and understand something that hasn’t yet been created.”

These days, on large films—and even medium-to-low-budget-ones—various scenes might be animated first—including those that will be shot entirely in live action, Fink says. The director, director of photography and production designer work closely together to create these “pre-visualizations,” which sometimes are done for every scene in a movie. Even if there isn’t any animation on the screen, “pre-vis” animations may have been a key part of a film’s production.

To Infinity and Beyond

USC was the first major university in the country to teach animation. The course began in 1933, only four years after USC inaugurated the country’s first class on filmmaking. The animation instructor—Boris V. Morkovin, a sociology and comparative literature professor—brought Walt Disney himself to campus to talk to his classes. In turn he gave lectures to animators at Disney’s studio.

Today USC instructors still teach hand-drawn animation, but they also offer students the latest technology, including tools for stop-motion and 3-D digital modeling. Last spring, Hench division professor Eric Hanson—a former special effects artist for big-budget films—created the first studio class to use USC’s own IMAX theater. Undergraduates shot three short films, each designed for a different immersive experience: an IMAX theater, a full-dome theater and the Oculus Rift virtual reality headset.

During his eight years at USC, Hanson has unleashed new digital avenues for students in lighting, compositing and visual effects storytelling. Hanson’s own work epitomizes the limitless possibilities of combining live action with animation. He travels to remote, inhospitable destinations around the globe, such as glaciers in Iceland and the Himalayas, and records the landscape with cameras, laser scanners, camera drones and helicopters. The former competitive hang glider pilot then assembles thousands of images taken at extremely high resolution and creates immersive video environments that surround viewers with panoramic images roughly 1,000 times more detailed than what a conventional digital camera captures. “You see things that would be impossible to see if you were actually there,” Hanson says.

It’s a far cry from hand-painted cels, but it’s still considered animation.

Other new genres of animation include Japanese-inspired anime, documentary animation and the “visual music” created by Hench professors Mike Patterson and Candace Reckinger. As innovators in this area, the two are known for the elaborate projections they and their students create to accompany live performances by orchestras and other musical groups. It’s a mix of 2-D and 3-D animation, illustrations, live-action photography and stop-motion animation.

“We’re melting the borders between film, animation and music,” Patterson says.

To consider the world that’s opened to animators, look at the career of Raqi Syed ’98, MFA ’01. She has worked on more than a dozen big-budget films, including ones immediately recognizable as animated (The Adventures of Tintin, Tangled) and others considered live action (Avatar, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, Iron Man 3 and The Hobbit films). Going by the title of lighting technical director, she’s an expert on bringing characters and environments to life with realistic applications of light and shadows. “We think of ourselves as digital cinematographers,” she told animation students during a recent visit to the University Park Campus.

Syed considers any film that is manipulated frame by frame an animated film, and notes that visual special effects are increasingly being used in subtle ways outside obvious summer action blockbusters. “Birdman, for example, had an interesting set of contradictions,” she says. It was lauded for its seamless long takes that didn’t rely on special effects. But in truth, she says, “a lot of it was digitally stitched together.”

Animators constantly hear complaints that computer-generated imagery ruins films, something Syed attributes to society’s discomfort with technology and feelings of nostalgia for the past. But animation and effects are improving at a dizzying pace, giving film creators greater control than ever, she says. “What visual effects were five years ago aren’t what they are today.

Spanning the Uncanny Valley

USC cinema history is studded with early technical wizards such as Ray Harryhausen, whose puppet animation in the 1953 film The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms began the monster-movie genre. Harryhausen, a former USC student-turned-lecturer who died in 2013, also created the stop-motion Sinbad fantasies and special effects for influential films such as Jason and the Argonauts in 1963 and the original Clash of the Titans in 1981.

Those crude animations are worlds away from the current photorealism in animation that inches closer to the so-called Uncanny Valley, the phenomenon of human characters looking creepier the closer they get to looking real. The Uncanny Valley may be the biggest stumbling block in the movement to bring animation and live action together.

“We will accept cartoony people, but a nearly photorealistic person can leave us feeling unsettled and pull the audience out of the story,” explains Richard Weinberg, the computer scientist and research associate professor who helped design the School of Cinematic Arts’ original MFA program in film, video and computer animation. Current off-the-shelf and real-time computer models aren’t good enough to perfectly re-create human features, so the “nearly human” animations make people uncomfortable. But expect that to change as computer modeling improves, says Weinberg, the Charles S. Swartz Endowed Chair in Entertainment Technology.

The technological bridge over the Uncanny Valley might very well be built at USC. Weinberg credits the work of USC Institute for Creative Technologies’ Paul Debevec for the development of light stage technology to capture live actors. Debevec’s system creates digital doubles that in many cases are indistinguishable from real people, with lighting that blends easily into the movie.

The Uncanny Valley is also being tackled by Hao Li, a USC Viterbi School of Engineering computer scientist lauded as one of the world’s top young innovators for his work on facial recognition and capture.

“I don’t think that anywhere else in the world is there a more intense agenda on creating virtual humans and worlds,” Li says. In collaboration with Oculus Rift, his lab has developed the first headset that can detect a wearer’s facial expression in real time, enabling people to interact with each other in virtual reality. The lab also digitized high-fidelity human hair from a single image, a technological feat. His next push is for technology to help digitize the full human body with clothing.

In the near future we also can look forward to fully immersive 3-D videos and games, rendered in real time and indistinguishable from reality, Li says. And animation itself will become even more automated and accessible. “It is likely that someday, everyone can become a professional animator, just like we can produce professional-looking images through Instagram filters using a simple click.

“Animation is an art form that people create from scratch,” Li says. “The horizons for it are just limitless.”