Designs on Social Change

Creativity can combine with business principles to solve societal challenges—and turn a profit.

Chop. Chop. Chop.

The woman dices onions and peppers and tosses them in a bowl. They’ll soon become part of her ceviche, a seafood mélange that will feed her family of seven.

Her strong hands have prepared their share of meals in her tidy home in Lamont, a heavily immigrant farm town in California’s San Joaquin Valley. The passing of time here is marked not in sunrises and sunsets but in how many stockpots of beans she’s cooked. But today is different. She pauses, puts down her knife, wipes her hands and sits down.

Someone has come to listen to her story.

The two USC students at her kitchen table, Angeli Agrawal and Natalie Tecimer, traveled more than 100 miles to learn about a rhythm of life different from their own. In Spanish, they talk about picking grapes, emigrating from Mexico, the value of education and the family’s recent health struggles.

I wish we could stay longer, Agrawal thinks. But they have to get back to Los Angeles.

After two nights, the pair and their 18 classmates return to USC on a mission. They’ll use what they’ve learned to try to improve health among the rural poor.

The students won’t bring change through social programs. Instead, they’ll use their creativity and the tools of business.

Design Thinking

The students are part of the Social Innovation Design Lab, a hands-on course in the USC Marshall School of Business that teaches undergraduates to combine “design thinking” and business principles to make a better world. Students envision and create prototypes of affordable products, from breathing masks to nutrition-themed toys, that could boost health while sustainably turning a profit.

Kicking off in January, the course grew out of the Society and Business Lab, USC Marshall’s program that uses business to alleviate poverty.

In the late 2000s, Society and Business lab founder Professor Adlai Wertman and Abby Fifer Mandell, the lab’s executive director, tossed around the idea of a program that could teach students to create a beneficial product and take it to market. Their recent partnership with Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, Calif., and its “Design Matters” program made it possible. Now USC and Art Center exchange graduate-student instructors for their courses.

Wertman and Mandell also enlisted creative minds from the international design firm Continuum to run a student workshop on design thinking. And in the San Joaquin Valley, the Dolores Huerta Foundation, a community-organizing group, placed USC students with families so they could learn firsthand about health issues common among farm workers, such as chronic asthma and limited access to doctors and dentists.

Even the course’s funding is creative. it’s supported by a grant from the National Collegiate Inventors and Innovators Alliance and an innovative-teaching award from the USC Office of the Provost.

Students competitively apply for the class. With the understanding that the most difficult social problems need interdisciplinary approaches, they represent different majors. The first course includes artists, engineers, and students studying business, cinema and social sciences.

“This is the only class I’ve ever taken that’s so interdisciplinary,” Agrawal says.

Learning Firsthand

USC students Scott Fairbanks and Petey Routzahn stare out the windows of a hatchback as they trundle west on a dusty farm road in Weedpatch, Calif. The 1940 classic The Grapes of Wrath was filmed here.

An 18-wheeler passes. “Another Coke truck,” Routzahn says.

They’ll see a lot of soda over the weekend. The USC students notice other things, too—the child who eats bacon-wrapped hot dogs for breakfast and the families that avoid drinking from the tap due to arsenic in the water supply. The students jot down notes.

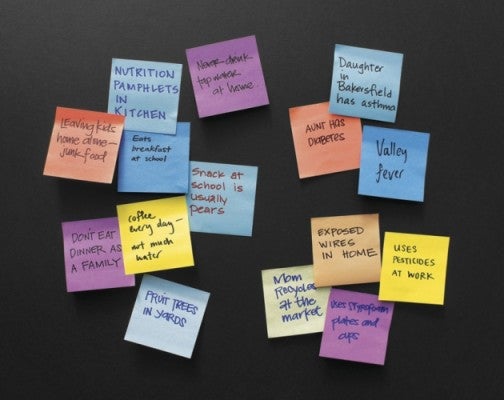

As the weekend ends, the young men and women come together and share observations, writing them on yellow sticky notes and slapping them up on a wall. Insights into the residents’ health start to take shape among the yellow squares.

They combine that with what they know: The U.S. Census indicates that 30 percent to 40 percent of residents here live below the poverty line. The area has among the nation’s worst air quality, according to the American Lung Association. Domestic violence, teen pregnancy, diabetes and obesity rates are troubling. The list goes on.

Students strive to empathize with families without judgment.“your role,”course assistant Mariana Prieto tells them, “Is to understand people and their needs.”

Through big groups and small, class members identify challenges to residents’ health and decide which ones they’ll tackle through product design. energized, they map out their ideas on pages of butcher paper, but some quietly wonder, Can I do this?

Turning Ideas Into Reality

It’s midterms week in March, and young men and women are lugging cardboard boxes, plastic gizmos and drawings into Davidson Conference Center at USC. They’re presenting their prototypes to instructors and designers for feedback.

There are lots of opportunities to make a difference. Fairbanks’ and Routzahn’s team, for one, tackles exercise. They present ideas for inexpensive toys that can bring communities together, a machine that dispenses sports equipment and a chair that makes TV viewers work their ab muscles while seated.

Agrawal’s team, meanwhile, believes in boosting health literacy. She and her partners propose solutions to help Spanish-speaking patients better communicate with doctors and pharmacists.

“Fantastic presentation, you’ve got a very clear mission,” says Art Center faculty member Penny Herscovitch.

Wertman, professor of clinical management and organization, looks on with pride. The students already have delivered more than he ever expected. Soon, they’ll learn about manufacturing methods and refine their ideas.

“Most of our students are in business school to learn the tools,” Wertman says. “It was thought that if you wanted to save the world, you would have to solely learn about policy, social work or maybe international relations.

“We believe you can use business skills to do it.”