Illustrations by Chris Gash

Interventional Cardiologists and Radiologists Heal From Inside Out

Minimally invasive techniques to treat diseases helps patients recover more quickly and safely.

Even into his late 80s, Angelo La Bruna Sr. regularly drove the 22 miles to USC’s Dedeaux Field from his Hacienda Heights home to watch his grandson Angelo La Bruna ’15 play baseball. Anyone would expect that he might feel a little tired making the trip. But when the active octogenarian started having chest pain and couldn’t catch his breath walking to the bleachers, he headed to the doctor.

Turns out it wasn’t fatigue. Just before his grandson graduated and was drafted by the Washington Nationals, the senior La Bruna learned that his heart’s aortic valve was narrowing. His physician, Ray Matthews, an interventional cardiologist and chief of cardiovascular medicine at Keck Medical Center of USC, diagnosed him with aortic stenosis, one of the most common, and most serious, heart valve problems people can face. When found, it usually requires surgical valve replacement.

Daunted by the prospect of the increased risk with an open-heart operation and an extended recovery, La Bruna was delighted to hear there was another option. He was a good candidate for a treatment that might have once seemed like science fiction. Matthews and Vaughn Starnes, a heart surgeon and chair of the Department of Surgery, inserted a new valve into La Bruna’s heart while it continued to beat—without ever opening his chest.

Physicians call the procedure a transcatheter aortic valve replacement, and it’s one of the many ways they can now treat patients from the inside out.

Keck Medicine of USC specialists are part of the growing field called interventional medicine. Interventional cardiologists, interventional radiologists and vascular surgeons can insert tiny tools and devices through small slits into the body and maneuver them to where they’re needed by using humans’ natural freeway system: blood vessels. Many patients in these procedures need only local anesthesia and can go home more quickly—in some cases the same day—with the opening in their skin covered by a Band-Aid. The technique also offers treatment options for patients too sick for major surgery.

In La Bruna’s case, Matthews and Starnes inserted a flexible catheter through a tiny incision in the groin and guided it into the femoral artery, then threaded it up to La Bruna’s heart. They then painstakingly installed a new valve through the tubing.

Interventional cardiologists like Matthews work with primary cardiologists and cardiovascular surgeons to see, evaluate and treat narrowed arteries and weakened heart valves. As part of a multidisciplinary team, interventional cardiologists aim to formulate the best treatment plan for each patient. Then they use imaging guidance and a variety of instruments, many as small as a few millimeters wide, to do their healing work.

While the specialty of interventional cardiology isn’t new, Matthews says its techniques have expanded and improved since the first transcatheter valve was approved for use in 2011. In the past, physicians treated valve problems exclusively through thoracic surgery, but today, many patients are candidates for the transcatheter approach, called TAVR for short.

“We are one of three medical centers in Southern California that began performing TAVR more than four years ago as an option for elderly patients who might be too frail to withstand open heart surgery,” Matthews says. “We’ve had great success with the procedure.”

And through a randomized clinical trial, Keck Medicine doctors recently started offering TAVR to lower-risk patients who have stenosis in the aortic valve that’s severe enough to cause symptoms.

Interventional cardiology’s next big leap could bring similar repairs for patients with mitral valve stenosis or leakage. Physicians are already evaluating several transcatheter mitral valve repair devices in patients through clinical trials.

“With cardiovascular disease being the leading cause of death in the United States,” Matthews says, “I see interventional strategies being used not just to treat cardiac conditions but also to see how best to prevent them.”

Interventional medicine reaches beyond the heart. It benefits cancer patients too. Physicians use their interventional techniques to steer cancer treatment exactly where it’s needed.

Jerry Chong, 72, can testify to that. He was treated 18 years ago at Keck Medical Center for liver cancer through a catheter procedure called a transarterial chemoembolization. That treatment began with an angiogram, an X-ray that physicians use to see blood vessels in action. The test identified the vessels that were nourishing his liver tumor.

As Chong lay still, his interventional radiologist followed live X-ray images on a monitor to guide a catheter from his groin to the liver. Doctors injected a combination of chemotherapy drugs through the catheter into the blood vessels feeding his tumor, followed by an injection of tiny particles called microspheres. The microspheres created an embolism: They plugged the blood vessels, blocking oxygen-rich blood flow to the tumor and bathing the tumor in chemotherapy drugs.

“Doctors told me that I had a tumor the size of a fist,” says Chong, of Encino, California. “I was lucky it didn’t metastasize and they were able to shrink it successfully.” He still returns every six months for follow-up visits, with no cancer recurrence.

Edward Grant, chair of USC’s radiology department, notes that interventional radiologists use their techniques in the treatment of various cancers, and their mastery of imaging tools like X-rays, ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging helps them see and target tumors.

Through interventional radiology, physicians can use embolization to shut off blood flow to kidney tumors, for example, and reduce the risk of bleeding during surgery to remove these tumors. Physicians may also “burn” cancers from within by using radio waves or microwaves delivered directly to a tumor—a process called radioablation. Or they can “freeze” a tumor by super-cooling it, called cryoblation.

Grant says emerging technology may offer even more new tools to physicians in the interventional world. Through 3-D printing, interventional radiologists may be able to fabricate catheters and implantable devices in sizes and shapes customized to each patient. These include stents, coil-like sleeves that pop into place inside artery walls to keep vessels open and keep blood flowing.

But for many patients, like Angelo La Bruna, the interventional advances available today already have made a huge difference. Since undergoing his procedure, La Bruna regained the energy to keep up with his large family: his wife, four sons and 12 grandchildren.

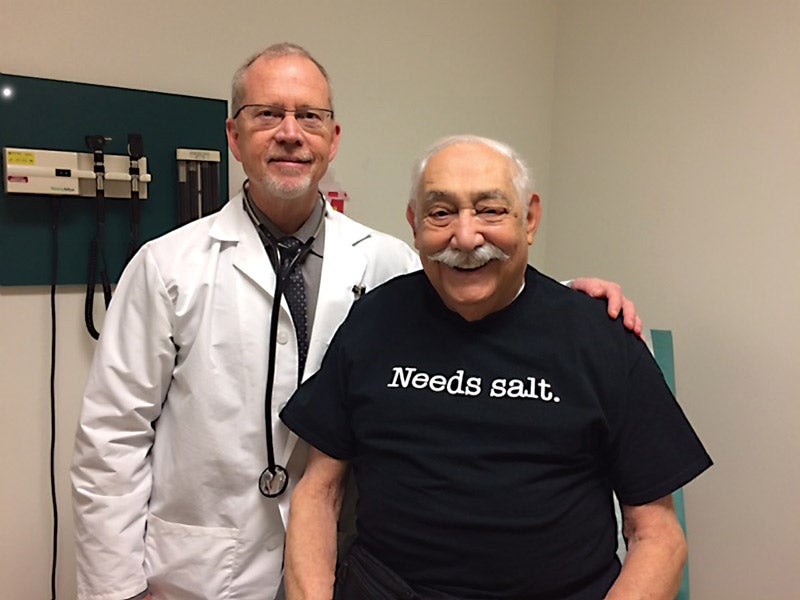

His only complaint is one about his diet, which he not-so-subtly broached with Matthews. He arrived at his annual follow-up appointment wearing a T-shirt proclaiming “Needs salt.”

“I just wanted to tease Dr. Matthews,” La Bruna says with a laugh. “I actually feel fantastic.”