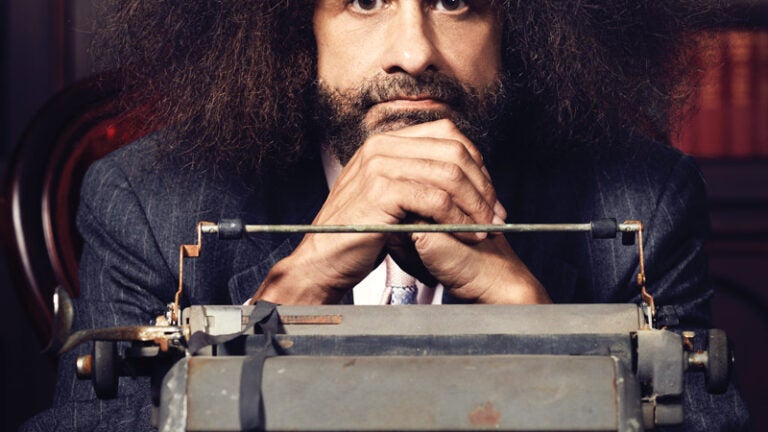

Jody Armour | PHOTO BY CODY PICKENS

Four Professors Find Purpose After Difficult Pasts

Meet four USC educators and researchers whose pasts motivate them to make a difference for others.

Police kicked down the door to Jody Armour’s family home in Akron, Ohio, late one night in 1967. As an 8-year-old boy, he watched bleary-eyed as they wrestled his father to the ground and shackled him. He would not see his dad freed from prison until he was a teenager. That dark night not only traumatized the Armour family; it also gave young Jody a mission in life. He would grow up to become a pioneer in spotlighting racial disparities in the criminal justice system; a vocal ally of the Black Lives Matter movement; a national thought-leader on law, language and philosophy; and a consensus-builder on diversity issues at USC.

Today, Armour is the Roy P. Crocker Professor at the USC Gould School of Law. Each day, the students in his criminal law class bear witness to his inspirational journey. There are others like Armour at USC. Professors who can directly trace their life’s work back to a moment of passionate clarity. Often, though not always, the moment is painful or unjust. But armed with imagination and intellect, they draw strength from personal experiences to make a difference in the world.

These are four of their stories.

[flipbook anchor=”jody” ids=”101797″ class=”no-lines”]

JOURNEY to JUSTICE

As the police searched his family’s apartment for drugs, young Jody Armour felt certain his dad would have the last laugh. A proud World War II vet who had fought at Iwo Jima, and the owner-manager of several family-run apartment buildings, Fred Armour was an upstanding citizen. In late 1960s Akron, the barrel-chested, 6-foot-8-inches tall man stood out. For some, he also stood out in a way that they didn’t like: He was a black man married to a vibrant, red-haired white Irish Catholic woman.“This was very transgressive of the social norms of the day, and upsetting to people,” Jody Armour says.

The mixed-race family—his mother, Rose Anne, had three white children from a previous marriage, as well as five children with Fred Armour—attracted stares and sneers on Main Street. “‘Nigga lover,’ that’s what I heard them call my mom so much,” he says. The ugly racial slur would become the initial working title for his forthcoming book, the culmination of 15 years of scholarship on race, language, law and ethics.

Fred Armour had no prior criminal record, but during that 3 a.m. raid, police purportedly “found” a 5-pound bag of marijuana in the kitchen cupboard. Based on this material evidence, the testimony of two drug users facing possession charges, and false statements from the prosecutor, Fred Armour was sentenced to 22 to 55 years in prison.

Determined to prove his innocence, he taught himself criminal law and procedure from books in the warden’s library. He became a skilled jailhouse lawyer and in his defense he crafted a novel legal theory—one upheld by the U.S. 6th Circuit Court in Armour v. Salisbury—barring prosecutors from deliberately misleading a jury. After six years behind bars, Fred Armour won his freedom—and helped a dozen other inmates gain their own release as well.

In his absence, the family unraveled and plunged into poverty. But young Jody caught a break: He qualified for a national scholarship program for disadvantaged youths that sent him to a first-rate boarding school in Philadelphia, where he thrived. He went on to study philosophy and sociology at Harvard, then law at UC Berkeley.

His dad’s ordeal had left Jody Armour embittered but it also instilled in him the power of words. “All he had, between him and rotting in a jail cell for life, was this typewriter—which I still have—and these words,” he says of his father. “Through word-work alone, he was able to find the key to his jail cell.

“That stuck with me.”

Today, Jody Armour teaches his father’s case in his criminal law course. He also publishes extensively and is a leading media expert on racial injustice in the criminal justice system. His 1997 book Negrophobia and Reasonable Racism anticipated many of the Black Lives Matter movement’s arguments. Now his forthcoming book takes those ideas to the next level, drawing on a USC Gould course he teaches on law, language and ethics.

Last fall, as diversity and free speech issues swept across the nation and college campuses including USC, Armour brought his expertise to bear on USC’s newly formed Provost’s Diversity Task Force. The 10-member working group—made up of students, faculty and administrators—has gathered twice weekly since last November, single-mindedly focused on improving USC’s culture of inclusivity. Armour volunteered to serve in the group and has been praised for bringing unity and openness to the effort.

“This is a moment unlike any I have seen in the 20-plus years I have been in academia and around cultural and racial issues,” Armour says. “USC has benefited from having students who are dialed into the zeitgeist with calls for more diversity, inclusion and social and racial justice. But we also have a convergence of those student sentiments with equally strong sentiments by the university leadership. I am skeptical by nature, but what I’ve seen this year is a real basis for optimism going forward.”

The injustice of Fred Armour’s years in an Ohio penitentiary can’t be undone. But his legacy—marshaling words in the quest for racial justice—wins new victories every day through his son.

[flipbook anchor=”nicole” ids=”101813″ position=”left” class=”no-lines”]

COMING HOME

Nicole Esparza never knew her grandparents. They kicked their pregnant 16-year-old daughter out of the house before Esparza was born. But she knows homelessness: She bounced between rescue missions and emergency shelters in Oakland, California, as a child.

She also knows the foster care system. Esparza’s mother, pressed to choose between her boyfriend and the child he didn’t want to raise, handed the girl over to the county social services agency when she was 5.

Esparza spent six frightening months in an institution for homeless youths. Four kids to a room. Bullying and fights. No privacy.

Then something amazing happened: On the very first try, she was placed with the perfect foster family. She finally knew love.

Trish and Will Esparza desperately wanted children but couldn’t have any of their own. They came to adore their foster kids and adopted all three.

“My story is a happy one,” says Esparza, an associate professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy, where she directs the graduate program in nonprofit leadership and management. “It’s easy to say the system isn’t working and sometimes hard to see when it does work. I can honestly say it worked for me.”

Everyday routines that other kids took for granted were precious to Esparza: flute lessons, playing on the basketball team, just being part of a family. “What I loved most about my childhood is that we would always eat dinner together and then watch TV. ”

Money was tight and her dad worked two shifts and lots of overtime cleaning planes for United Airlines. Her mom juggled parenting with part-time clerk jobs. Once Esparza was old enough to work at the mall, she pitched in to help pay the mortgage. They came close to defaulting several times, but they never moved, Esparza says proudly. “No matter what, we were always able to somehow keep our house.” For someone born into homelessness, that was huge.

There were other struggles, though. Their Oakland neighborhood was plagued with gang violence, and her brother spent time in juvenile lockup. Esparza, a top student, was the only one in the family to earn a high school diploma and go on to college.

One of Esparza’s first classes at UC Berkeley focused on homelessness. The course required an internship, so she made a brave choice. She returned to the transitional youth center she’d been assigned to after her birth mother relinquished her. Counseling teens, Esparza was struck by their resilience. “I can’t imagine myself being that strong,” she says, “but I must have been.”

Esparza volunteered at the center throughout college and remained as a paid staff member for five more years until she headed to graduate school in sociology at Princeton. She later had a two-year stint as a Robert Wood Johnson Scholar at Harvard.

Now Esparza is on a mission to discover what works in social services, and why. Inside the plans and year-end reports of rescue missions, homeless and domestic violence shelters and food banks, she believes, lies the key to social progress.

“The reason I’m interested in organizational structure,” she says, “is because it can work, and I want to see what is it that makes it work. How can we tinker to make it work better?”

In her latest journal article, she argues for finding permanent homes for the homeless. “We put money into temporary housing, emergency shelters and transitional places, but it doesn’t solve anything,” she says. “Now we’re realizing the homeless would do a lot better if they didn’t have to come back day after day.”

She stays connected with foster-care trends as a much-requested graduate advisor at USC Price and the USC School of Social Work, where she serves on 10 dissertation committees. “This is why I really like working at USC,” she says. “I’m a bridge between people who do housing and people who do policy.”

Today, Esparza lives near Los Angeles’ Skid Row with her 8-year-old daughter. “Frances is the only person in my life who I’m actually blood-related to. My daughter acts exactly like me, thinks exactly like me.”

There’s one big difference. Though her daughter has learned all about homelessness, she’s never had to experience it firsthand.

[flipbook anchor=”janos” ids=”101815″ class=”no-lines”]

HOPE for HEALING

Some people are born to be doctors, but János Peti-Peterdi’s destiny was much more specific. “My fate—to perform kidney research—was determined before I was born,” says the renowned kidney disease expert and renal physiologist. From childhood, he was driven to find a cure for chronic kidney disease—the life-threatening condition that afflicted his mother, Erzsébet Vármos.

Their story begins in the family home in Csurgó, Hungary, where his mother caught strep throat as a teenager. Unfortunately the complications went undetected and untreated, leading to severe kidney damage.

“It’s a miracle she survived,” says Peti-Peterdi, a professor of physiology and biophysics at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “Even my birth was a miracle.”

Newly married and expecting her first child, his mother was admitted to the regional hospital with acute kidney disease. Doctors terminated her pregnancy and offered bleak hope for recovery.

“They were actually running human experiments on her in the basement,” says her son, his voice rising with indignation. Dialysis hadn’t reached Hungary yet in the early 1960s, and there were no known therapies for kidney failure. But the thought of physicians exposing her to random drugs still enrages Peti-Peterdi.

Luckily his mother was—and still is—a fighter. Late one night, she disconnected her tubes and escaped by train to a more enlightened nephrology clinic in Budapest, where months of superior care stabilized her.

She would go on to have two healthy pregnancies, and both of her children ultimately became physicians.

There would be more relapses and hospital stays—lasting months, sometimes a year. At home, she suffered from debilitating fatigue. But her husband and children adored her. “My mother was always the center, the strength, the engine of our family,” he says.

As a young boy, Peti-Peterdi made rounds on the farm collecting blood samples from frogs, chickens and rabbits. He would examine them under a microscope, dreaming of someday curing his mother’s disease.

Today, his lab still uses microscopes, but they’ve advanced since his childhood. His high-tech scopes enable him to see living kidney tissue from mice—healthy and diseased—in great detail and in three dimensions.

Observation is key, because the healthy kidney has the ability to repair itself. “We would like to better understand how that intrinsic repair happens, and see if we can augment that, maybe even cause a regression of kidney disease. That’s our concept,” he explains.

A third of all patients with diabetes develop kidney disease, he says, as do many people with metabolic disorders, immune and inflammatory diseases or hypertension. Two National Institutes of Health grants worth about $5 million support his work. In 2015, he received the Young Investigator Award of the American Society of Nephrology and the Council on the Kidney of the American Heart Association.

As for his mother’s journey, it still isn’t over.

After enduring every complication from chronic kidney disease, she reached the end stage as her son was finishing medical school.

“She’s a survivor,” Peti-Peterdi says. “That’s the bottom line. Every single one of these complications is life-threatening. People usually die.”

His mother was approved for a kidney transplant in 1995, when her son was already working as a nurse at the Budapest clinic where she would receive her donor organ. With the new kidney, everything changed. “She became a normal, healthy person. The kidney works perfectly after 21 years,” he says.

But five years ago, she abruptly sank into dementia, believed to be a result of the many kidney-related complications she endured. At age 73, she no longer recognizes her family. But Peti-Peterdi soldiers on.

Though the once-precarious condition of his mother’s kidneys no longer keeps Peti-Peterdi up at night, his mission hasn’t changed. His team is developing a new concept and therapeutic approach that he believes will lead to a breakthrough.

“Almost every day, when I wake up, this is the question I ask: What can I do today to find a cure for this devastating disease?”

[flipbook anchor=”ruth” ids=”101816″ position=”left” class=”no-lines”]

CALL for COMPASSION

Though she was born in London and spent her teens and early 20s in Canada, Ruth C. White speaks with a lilting accent that is unmistakably Jamaican. So it was little wonder she felt drawn to the young Jamaican man named Everton who was her coworker at a trendy Ottawa clothing store. They became close friends. “I was the keeper of his secrets,” says White, a clinical associate professor at the USC School of Social Work.

Few others in their Afro-Caribbean expat community knew Everton was gay, and today, she doesn’t disclose his last name out of a wish for privacy. When Everton fell sick in the 1980s, there was no name yet for his disease, but White had read about the illness devastating so many gay men. Within a few months, Everton had died. At the funeral their mutual friends grilled White for information. She kept her silence.

“Jamaicans have a history of vehement anti-gay sentiment,” she says. “I felt if he didn’t tell them in life, I shouldn’t tell them in death.”

Later she heard that his family had burned Everton’s belongings. White’s crusade for the health and dignity of Jamaican homosexuals began that day.

She returned to college and became a social worker in Toronto’s juvenile prison system. Wanting to make a difference on a policy level, she pursued a PhD in social welfare and a master’s in global public health at UC Berkeley.

The ravages of HIV/AIDS were in plain view where she lived in San Francisco during the 1990s, but White’s dissertation took her back to Kingston, Jamaica, where gays still lived in closeted obscurity. Hardly any public health data existed on the island’s LGBT community, so she set about gathering dozens of case studies in focus groups and one-on-one interviews.

As White listened to their stories, she realized she was looking at a “whole bunch of Evertons. I felt like literally I was working for Everton.”

Marginalized in Jamaican society, some LGBT people endured abysmal living conditions, she says, even dwelling in caves.

White’s findings attracted international attention. HIV-prevention research grants and consulting jobs took her around the world. Pro-bono legal defense teams from American law schools solicited her expert testimony for gay Jamaicans seeking asylum. Success led her to a tenure-track job at Seattle University.

All the while, White was wrestling with a serious health problem of her own. Having long ignored the encroaching signs of bipolar disorder, after her daughter was born in 1997 White fell into deep postpartum depression. “I was in a dark hole for about a year,” she says. She waited five years before furtively trying talk therapy and then starting medication. It wasn’t enough. Fearful she might harm herself or her daughter, White voluntarily admitted herself to a psychiatric hospital.

There, she came to realize that with mental illness, as with HIV infection, hiding and silence are actually high-risk public health behaviors.

So she told her own story. “There was a whole body of literature about coming out in the classroom as gay, but there was nothing about mental illness,” she says. White bravely penned a chapter in a scholarly text detailing the struggles of mental health practitioners who suffer from mental illness. She went on to write two popular books on bipolar disorder from a first-person perspective. She blogs on culture and mental health for Psychology Today.

In her forthcoming book, White takes on the mantle of “health coach” and lays out her holistic system for managing chronic mental illness using “an immunization model” geared toward prevention rather than treatment. She manages her own symptoms with medication, talk therapy and her holistic approach.

A member of USC’s faculty since 2013, White lives in Oakland, California and teaches remotely for the School of Social Work’s online program. Her work lets her reach students all over the country without the travel-related stress that can trigger her disease.

Looking back, White sees a thread connecting her first inspiration—championing Everton and other gay Jamaicans—and her public battle with bipolar disorder. Her life’s work boils down to a simple imperative: Break the silence.